On reading the ‘Introduction’, Chapter Two ‘Thinking Like a Computer’ and Chapter Three ‘Thinking Like an Avatar’ from Steven Shaviro’s Discognition you begin to question ideas on consciousness and, more widely, sentience. Both concepts were initially interesting to me in the scope of my project concerning the human and the synthetic, the differences between the pre-supposed consciousness of the human and the sentience of the non-human. But is consciousness the pinnacle we as humans consider it to be? Here Shaviro posits that a process ‘that operates through speculation and extrapolation, and that takes place… in the future tense… is a kind of thought experiment, a way of entertaining odd ideas, and of asking off-the-wall what if? questions.’ (Shaviro, 2016, 8). This process is similar to how I have approached my Masters Projects so far, as a way to extrapolate or to infer an unknown from something that is known where thought experiments act as explorations outwards to ask questions about consciousness and the synthetic other. Shaviro also goes on to state that sentience itself employs a process of speculation and extrapolation. The basic modes of sentience have an aspect of generating ‘fictions and fabulations’ (Shaviro, 2016, 10), or inventions outside of programmed thought that can be extended to all organisms and artificial entities. Here Shaviro sets up this theory of ‘discognition’ that works as a disruptive act to extend and exceed cognition, but also extend under so as to support and enfold it. As such fictions and fabulations can be seen as a process, a process of speculating the unknown and the consequences that follow.

‘There has recently been a… dramatic shift in perspectives from input/output to output/input… Output tends to come first. Organisms engage with their surroundings with spontaneous actions, rather than just waiting for and responding to sensory inputs.’ (Shaviro, 2016, 13-14).

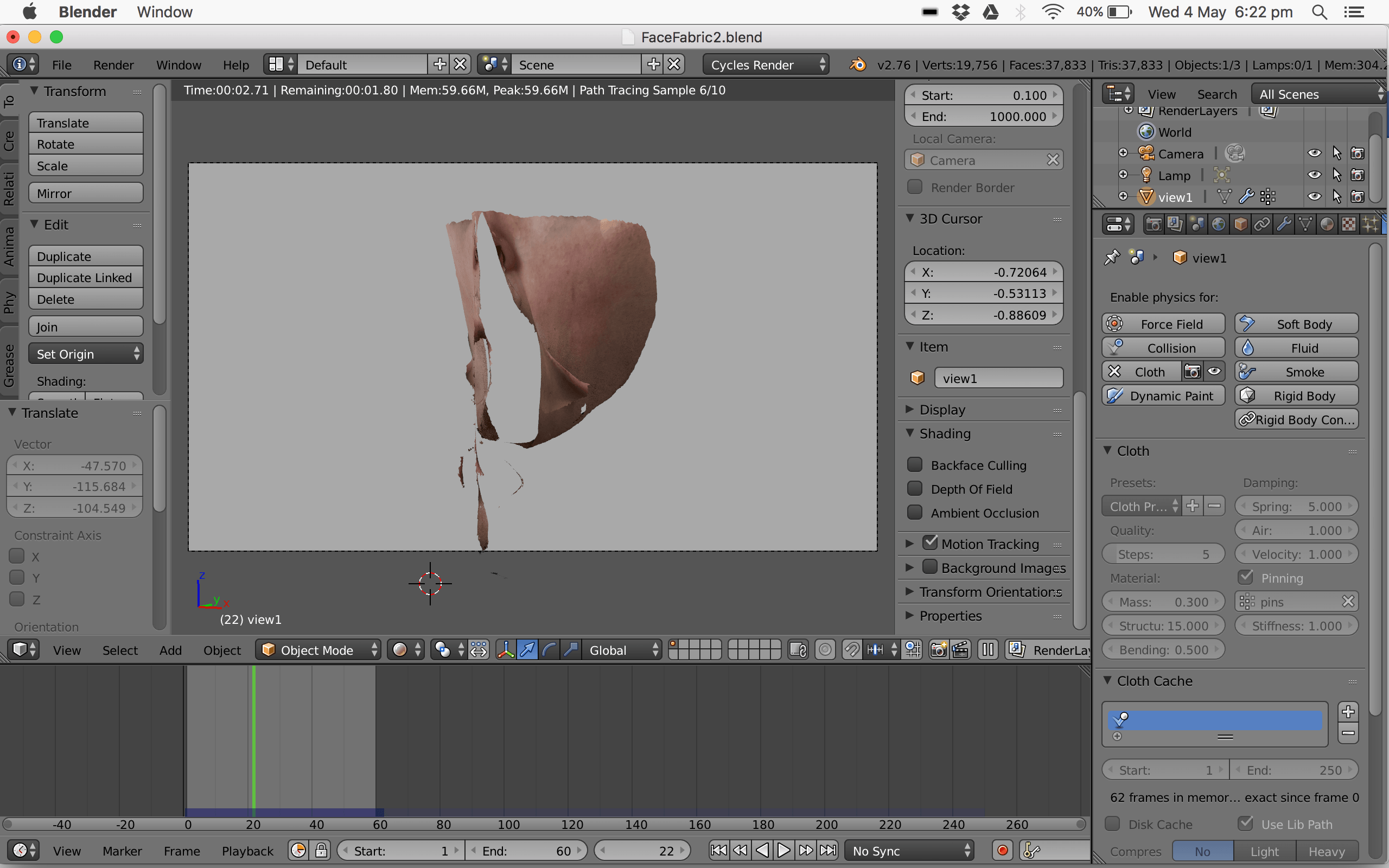

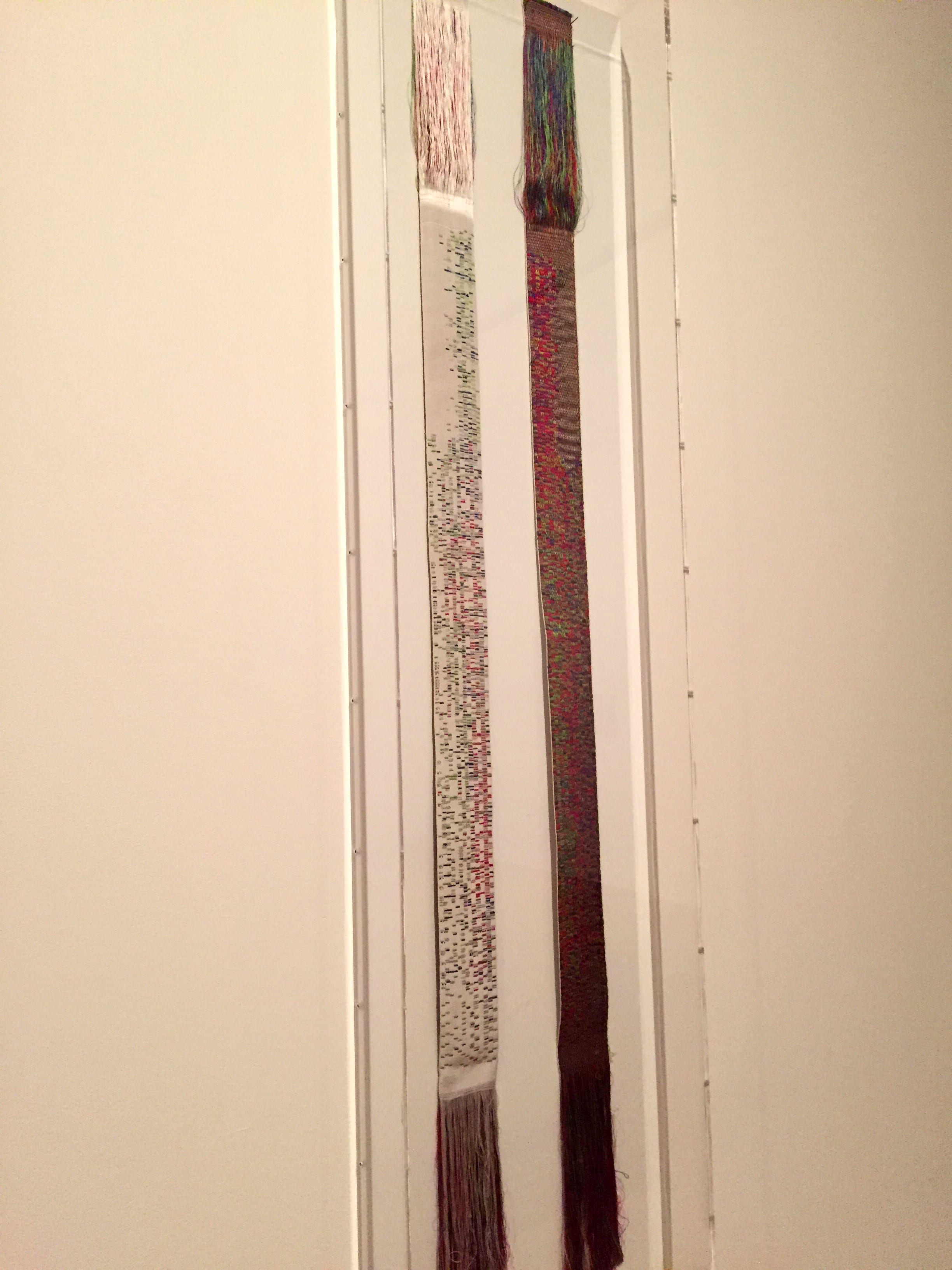

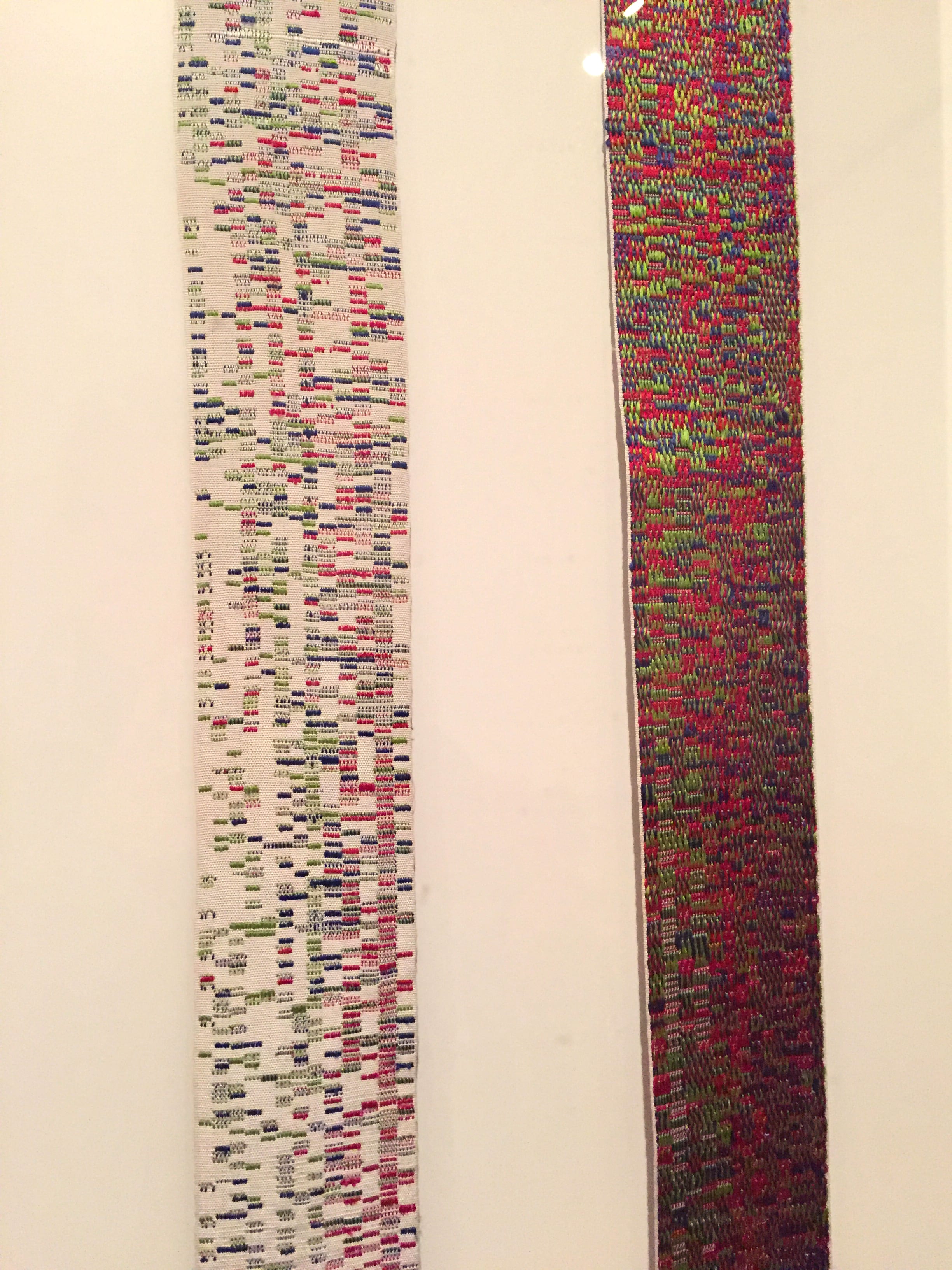

This output/input approach is interesting to consider where there is an active engagement by an organism with their surroundings, to probe the environment with spontaneous actions and evaluate the sensory feedback. Later in Chapter Two ‘Thinking Like a Computer’ Shaviro relates this process to the machine in a different way, Shaviro posits that the machine is not aware of the world and it does not use things in order to sense it but senses the things themselves. Here because the machine is operating and remaining within itself, the system’s own experiences are introspective and as such feeds back on itself. ‘What does it mean for everything to be data? Can DMS escape its own self-reinforcing feedback loops, and encounter something Other, something outside itself?’ (Shaviro, 2016, 54). The machine is thus an autopoietic system, a system that produced itself and through interactions and transformations continually regenerates and realises the network of processes that produced them. This closure is however impossible and ‘meanings are always leaking and contextual, slipping away from the systems that generate them’ (Shaviro, 2016, 55), self-generated understanding are therefore misleading and incomplete. However Shaviro goes on to suggest, as derived from Whitehead, that the primary meaning of life is the novelty of appetition, or the notion of looking and seeking after something. The machine will thus push limits, changing and seeking novelty or the speculation of the unknown. Able to envision, experiment and explore to push out against the limits of its own codification. This concept is pushed further in Chapter Three ‘Thinking like an Avatar’ in the consideration of artificial intelligence, software minds are always expanding to explore the phase space (or network) they inhabit and this isn’t limited by an organic body that has a point and a plateau where maturity is reached and development either slows or stops all together. The inorganic embodiment that the software mind inhabits allows for evolution at the same rate for their full life span. Shaviro goes on to state that intelligence is embodied but not just located in the mind, ‘it also necessarily involves some degree of extension into the outer environment, in the form of… the “extended mind”.’ (Shaviro, 2016, 95). It is entangled with its artificial extensions and prosthetics, therefore I can potentially view the objects created through Project 1 and Project 2 as being a part of this extended mind, they may be copies from an original that are then modified by their own lived experience, but they are entangled with human intelligence extending outwards.

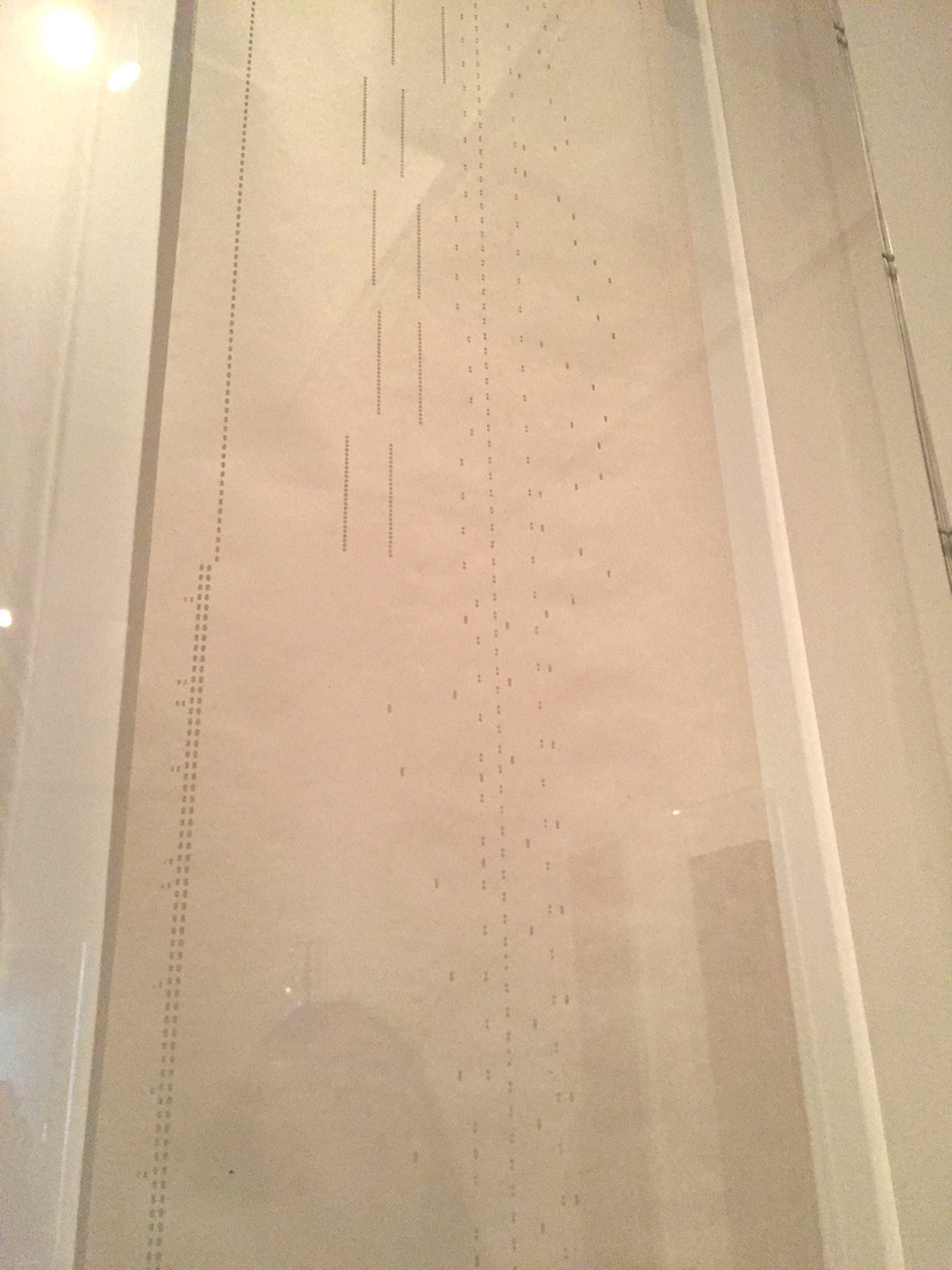

Perhaps even more fitting in relation to the ideas I have been considering so far, Shaviro discusses, in connection with Latour and Stengers, the scientific method of collaborating with non-human entities, to enter into an alliance with them (see also a union, an affinity, a state of being joined). These entities are not passive objects waiting to be dissected, they are active participants that need to be approached and incorporated holistically, equally systems function as wholes and their functioning cannot be viewed or understood solely in terms of their component parts. We can therefore suggest that science can never be purely human. This notion of collaborating with the non-human links with the notions of prosthesis and synthetic extension I explored through Project 2, perhaps there is scope to continue this line of enquiry to consider not just the physical but also the non-representation system in collaboration with the human. Including the notion of the system’s sentience interacting with human consciousness. If we consider sentience in the output/input approach previously discussed we can begin to see where we may be able to access these non-conscious forms, ‘fictions and fabulations can provide us with a sort of feed forward… of those mental processes that are not available for introspection’. (Shaviro, 2016, 16). Here Shaviro posits that non-conscious thinking is not available to us introspectively and we cannot examine this process, as it cannot be retained. Fictions and fabulations, or the process of reaching out to poke the environment, offer a feed forward approach to modify or control a process using anticipated results or affects. Thought and feeling are considered primordial affective phenomenon in the technical sense, ‘every entity becomes what it is by “appropriating” what is left behind by other entitles that precede it… an entity perpetuates itself by appropriating its own prior states of existence’. (Shaviro, 2016, 16). Here entities collect whatever they encounter to provide conditions for their own continued existence, this can be related to prosthesis and the additive notion of appropriating itself with the synthetic in order to continue its existence.

‘The code of a digient can easily be copied or cloned; similarly, in many science fiction works a brain state or mental state can be copied or transferred from one embodied entity to another, or even from an organic body to a dispersed computer network. But none of this obviates the necessity of generating the code or the brain state – by having the actual experiences – in the first place.’ (Shaviro, 2016, 78).

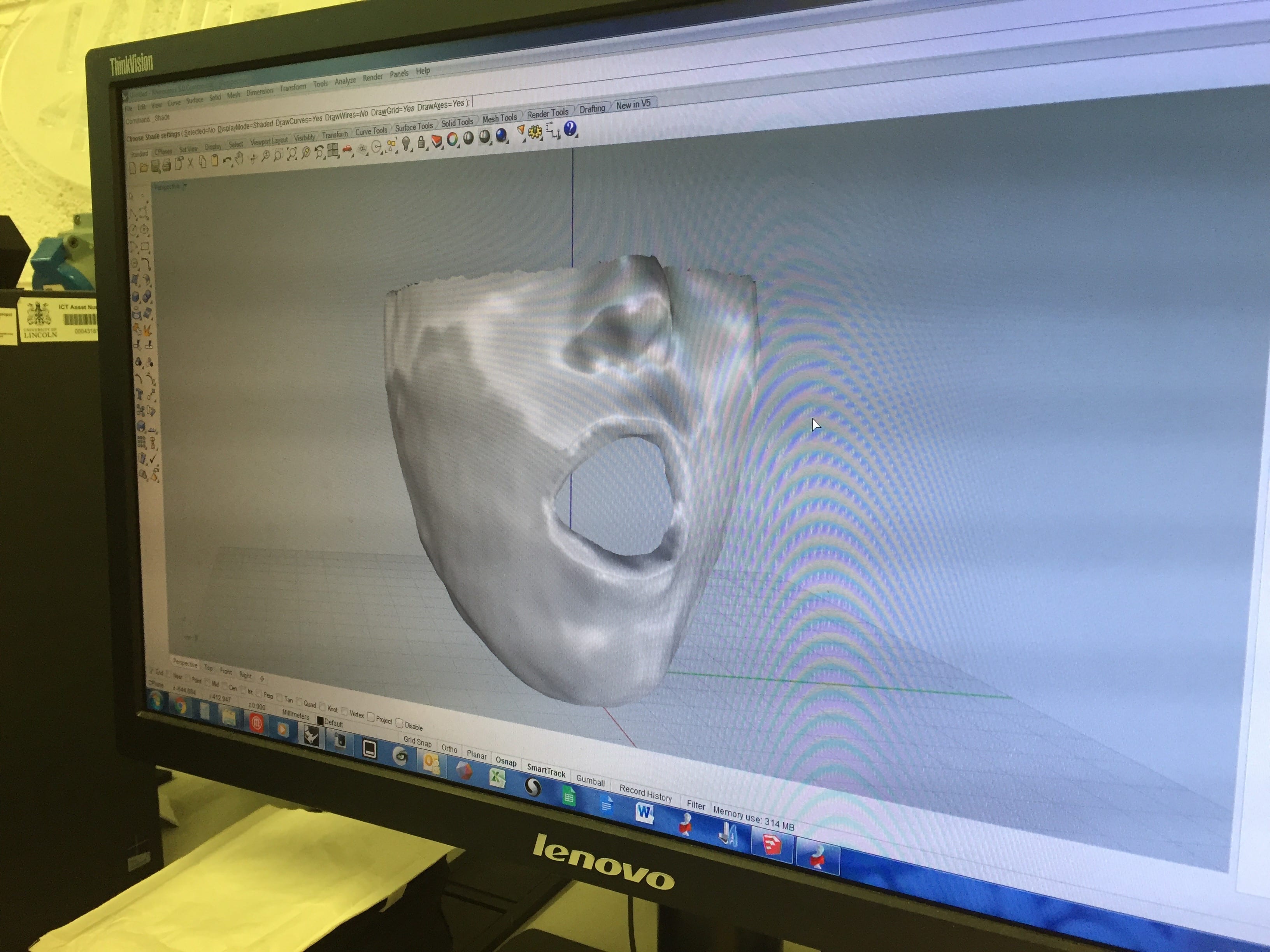

Shaviro is suggesting there is the requirement of an original in order to make a copy and to be able to transfer or disperse it to another or a network. This original requires the initial generating of a code or brain state, which then must learn and modify through lived experience, only then can a copy be made. This is at odds with Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto, whereby she posits copies without originals due to the nature of the breakdown of the border between the organic and inorganic, here the original is an intrinsic part of making a copy. Morehshin Allahyari’s thinking as part of her project ‘Material Speculation’ also differs with the view of originals being an essential aspect, Allahyari suggests that it is an illusion that things seem to continue on once they’re multiplied, dispersed and made visible across the network. In the absence of an original, copies of texts and images swarm around and form the missing thing as an imaginary concept of itself. These digital representations form the lost object, or the illusion of a persistent copy that evokes the original in a scaleless, placeless version without material conditions. (Allahyari, 2016). The copy in Sharivo’s point of view can then go on to be modified, it only shares the same identity to its original for a brief moment before its own experiences modify it and transform its identity. The copy must have this learning process as in essence the sentience of software is based on empty thoughts and blind intuition. We have seen previously that the machine is not aware of the world, it has no foundational experiences to guide it and as such it is alone, blind and deaf to it. The machine’s consciousness has empty thoughts and blind intuitions and yet perceives actively by being unstable with no fixed boundary, it reaches outward in an affective encounter with its environment.

‘You can always copy the final that instantiates a digient, and thereby get a new entity that is absolutely identical to its original. You can also “suspend” a digient (turn it off for a while, so that no subjective time passes for it), or even obliterate some of its experiences altogether’. (Shaviro, 2016, 81).

Perhaps this timeline or set of experiments could be incorporated into the output of Project 3? The entities could have the potential for the organic/ synthetic entities to be copied, to modify through lived experience, to be suspended and, ultimately, to be obliterated.